Behaviour in the home contributes to 50% of the energy consumption of the home. The study explored moderation of participant behavior and her willingness to adopt sustainable energy consumption habits. The study builds on DEFRA's research that established behaviour change as necessary to achieve a sustainable society. However studies of willingness to change are not evident. Policy continues to support Jevons Paradox that energy efficiency will not reduce energy demand. The study adapted a behavioural change tool developed by Stanford University's Persuasive Tech Lab. Community based social research recorded three sets of data; firstly, participant demographic and house-choice behaviour, secondly, participant environmental intent, attitude and behaviour, and thirdly participant willingness to change energy consumption habits. This study suggests attitudes changed to a motivated and willing state. The study proposes adapting the 'Behaviour Grid' for designers to motivate and raise a person's ability in support of willingness to undertake behaviour change.

Introduction

Behaviour in the home contributes to 50% of the energy consumption of the home (Sorell, 2009). While society's attitude and awareness surrounding energy-use has changed, energy-use behaviours appear to have not. There are two concerns with society's ability to consume less and differently in order for efficiency gains to be effective. Firstly, common policy assumed that sustainability through energy efficiency would reduce energy demand (Herring and Sorrell, 2009). In 1980 Khazoom and Brookes postulated further on Jevons Paradox of 1865 in support of neo-classical growth theory surrounding micro-economic supply and demand; efficiency reduced cost that supported growth. This led to an increase in the use of growth's associates and dependencies such as energy, which conflicts with a sustainable, equitable and just society. The second concern lies with the gap between a person's decision making surrounding her ethical consumption and her behaviour. A person's consumption actions are both a means and end, embodying her values and social actions out of convenience for comfort and cleanliness in the pursuit of a contemporary natural purity (Herring, 2009). A person's value-action gap is motivated by self-interest, social norms, habits, desire, approval, sacrifice, behavioural modes and concern for the common good. These two concerns contribute directly to the rebound effect in efficient home energy use, whereby a person more frequently maintains a higher level of thermal comfort for longer (Sorell, 2009). This places the designers of energy efficient buildings in a somewhat paradoxical position; are designers of energy efficient products, such as buildings, providing a solution or contributing to the problem and maintaining the status quo? If attitudes have changed, and behaviour has not, then is a person now actually more willing to live sustainably? How do designers support this willingness to change across their own ethical creative Value-Action Gap?

Background

This section has two aims: (1) to provide a short critical review of research to date, and (2) to provide a brief critical examination of factors surrounding the issue.

Frameworks, Attitudes and Behaviours

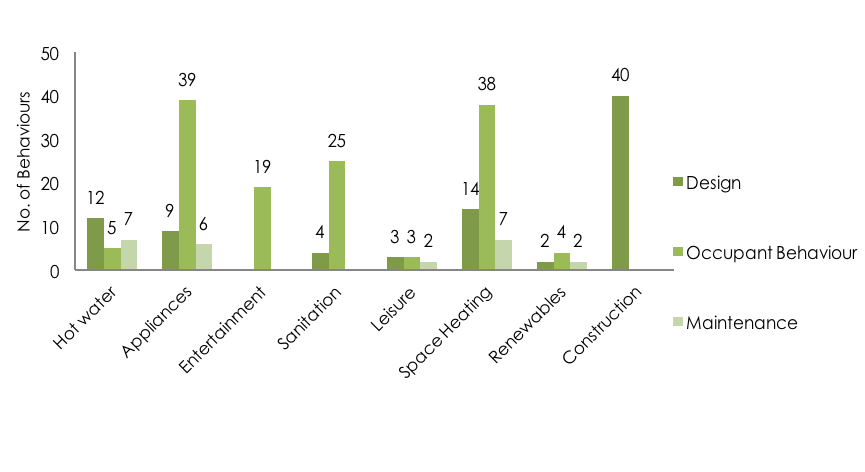

In 2007 the Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs and the Department of Trade and Industry concluded energy consumption in the home as the dominant area where a person's behaviour has the most negative environmental impact. Through a diffusion of responsibility, sustainable lifestyle was considered effortful and costly, with lifestyle choice seen as not contributory to climate change. The research suggested a person felt her individual liberty and freedom would be infringed upon in a less individualistic pursuit of a sustainable society. However a significant minority maintained that addressing the risk of climate change should be high on the national agenda. UK policy attitude shifted from how to support a person’s energy consumption lifestyle to concern with her energy consumption behaviour within her lifestyle. Analysis of barriers to lifestyle change determined DEFRA's seven population segments, which ranged from the 'positive greens' through to the 'honestly disengaged' that defined a particular policy response. The 2008 Queensland TRED Program identified 241 discrete residential energy-use behaviours that address hot-water energy, appliances, entertainment, hygiene, thermal comfort, renewable energy, retrofit and construction (McKenzie-Mohr, Hargroves, Desha, and Reeve, 2010). A brief view of the Townsville Residential Energy Demand Program attributes 10% maintenance, 35% to design and 55% to the occupant to affect energy-use behaviour change, as illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1 TRED Discrete Behaviours Distribution

Of the 30 one-off, habitual, regular or occasional behaviours identified by DEFRA, 18 were attributed to in-the-home behaviours, and 12 were considered to be 'headline' goals. Subsequently 3 one-off, 1 habitual and one occasional behaviour were promoted through policy; insulation of the home, micro-renewable energy generation, GETs, energy management and energy efficient products respectively (DEFRA, 2007).

The Challenge of Needs, Wants and Consumption

Attaining a sustainable society through changes in technology and its use in households must also focus on change in habitual behaviour that maintains social norms in fulfilling acceptable needs, but not wants. To meet her needs and maintain dignity a person requires food, clothing, accommodation, utilities and fuel, as well as household goods, personal goods and services, transport and activities that are social and cultural (Druckman and Jackson, 2012). Increasingly needs are subjected to obsolescence that exploits a persons dissatisfaction and informs her social context through the sign-value of manufactured objects that increase the rate of consumption. Reinforced through incentives, institutional barriers, and inequalities of choice, as well as habit, routine, social norms, expectations and values, a person's consumption has increasingly preceded her production in support of the debt based economic system (Baudrillard, 1996; Jackson, 2005).

Promoting Sustainable Behaviour

A person rarely acts out change in isolation as her acts are governed by peer-reviews of her values, beliefs and actions pertaining to social acceptance, which makes what may be perceived as delinquent behaviour, difficult on her part. A person is also a persuader and therefore contributing arbiter of social acceptance. It is this reflexive social interaction that is able to provide conspicuous consumption with a questionable status in contemporary transitional society. It is within this environment that it is possible to persuade a person to think through the implications of her energy use behavior (Corner, 2012). A person motivated to critique her behavior presents the opportunity to persuade in favour of change.

The Problem with Persuasion

The criticism of separating the person from her community is that this is seen to avoid addressing the complex dynamics of personhood in society, while assuming she has a capacity for action relevant to sustainable living which is more than reality provides (Brynjarsdottir, Hakansson, Pierce, Baumer, DiSalvo, and Sengers, 2012). A person’s behaviour is a compound of elements that form her sense of self, considered too complex to be tailored to a narrow view of sustainability, human behaviour and their interrelationship (Brynjarsdottir, Hakansson, Pierce, Baumer, DiSalvo, and Sengers, 2012). Modernist values of calculability, predictability, efficiency and control entailed a reductionist view of sustainability being taken into account when constructing persuasive arguments for behaviour change. Governments, NGO’s, business, media and individuals alike continued with sustainability communications that range from the fear inducing to greenwash that disempower a person's due consideration of a sustainable lifestyle given the threat of climate change.

Persuasive Systems for Sustainable Behaviour

A person is persuaded to socialise in increasing degrees through persuasive social media in various architectural settings, designed for salient self-shaping and commitment change with or without a person's knowledge (Moraveli, Akasaka, Pea, and Fogg, 2011). The Stanford University Persuasive Tech Lab recognised that a combination of a trigger with a person's motivation level and ability achieved measurable success through small step-changes that approximate the overall objective of lifestyle change (Fogg, 2009). Fogg drew on two traditions in psychology: (1) Social Cognitive Theory, Mindset and Attribution Theory, and (2) the Transtheoretical Model. The Fogg Behaviour Model defined types of behaviour change against time frames that are associated with a particular psychology and persuasion strategy for a persuasive technique to be mapped against. Fogg used simplicity as a means to increase ability so that whenever a person's motivation and ability placed her above her activation threshold, the correct trigger empowered her to do extraordinary and difficult things in order to change her behaviour.

Field Research Method

This study and prior research by DEFRA focused on suburban areas. DEFRA drew on four distinct geographic locations with 114 participants engaged (Brook Lyndhurst, 2007). A questionnaire was personally distributed equally amongst a random population sample in six residential areas of a single town to account for different attitudes and house types. Each area was seen as representative of the post-war architectural and economic period. The questionnaire was divided into three sub-sections: (1) the participant demographic and housing choice behaviour, (2) the participant’s lifestyle fit with her environmental attitude and intent towards the environment and sustainable lifestyle, and (3) the participant’s willingness to consider small step-changes to daily habits. The tests for willingness by this study adapted Fogg's Behaviour Model and defined as do you or would you do it if you could... for either one-time, one-time leading to an ongoing obligation, for a period of time, on a predictable schedule, on cue, at will or always. Each was considered in terms of familiarity, frequency, intensity and duration or stop and cease. This defined 35 small step-change catalytic behavioural goals. Although a response to a broad view of sustainability was asked for, specific statements tested Energy Performance Certificates, space heating, lighting, insulation, solar thermal energy and cost. Research variables not directly attributed to energy-use inform as to psychological attitudes surrounding energy-use in the home. The Likert-scale measure for willingness was considerable (1), moderate (2), some (3), little (4) or no interest (5). Of the 240 participants engaged, 88 returned responses at a time when energy security and 'fracking' in the UK was prominent on the national agenda during a period of particularly hot weather.

Findings

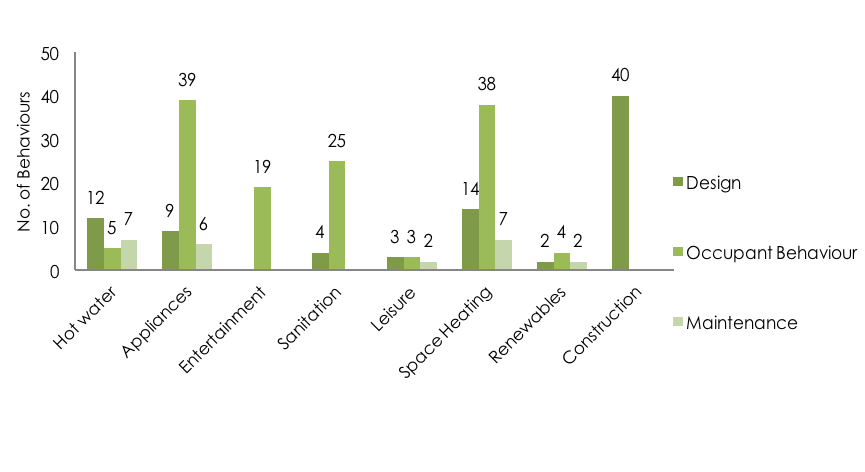

The engaged sample population was broadly representative of the UK population recorded by the ONS Census of 2011 and well educated and affluent. Results suggest that since 2007 participant-declared attitudes changed in favour of a more positive environmental behavioural attitude illustrated in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2 Participant Population Segment

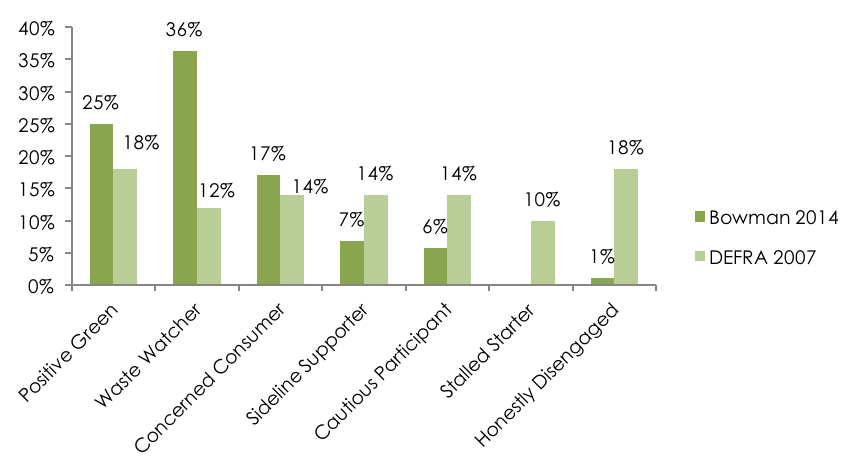

Cycling through the schedule-dependent behaviour goals as shown in Figure 3 below, revealed an increased change in willingness from some interest to moderate interest.

Figure 3 Behavioural Goal Mean Score across all Participants

68% of participants were unaware of the annual energy consumption in their home, and 14% of participants unaware of their monthly energy bill, however 57% support home EPC for informed future decisions regarding house purchasing.

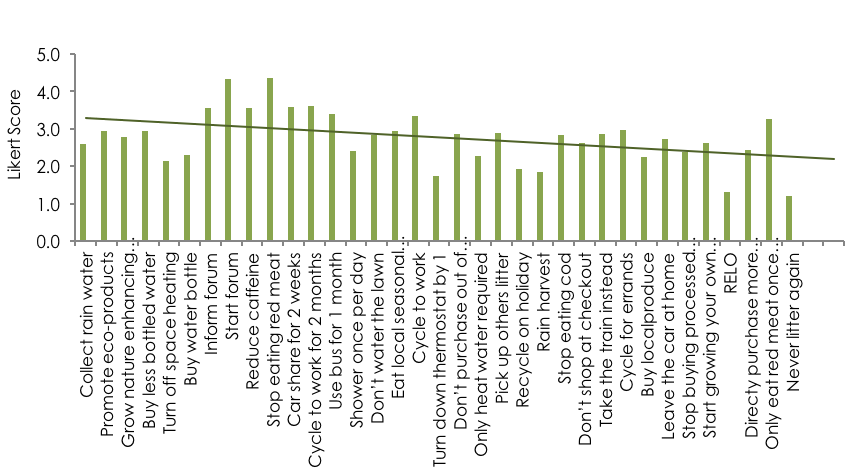

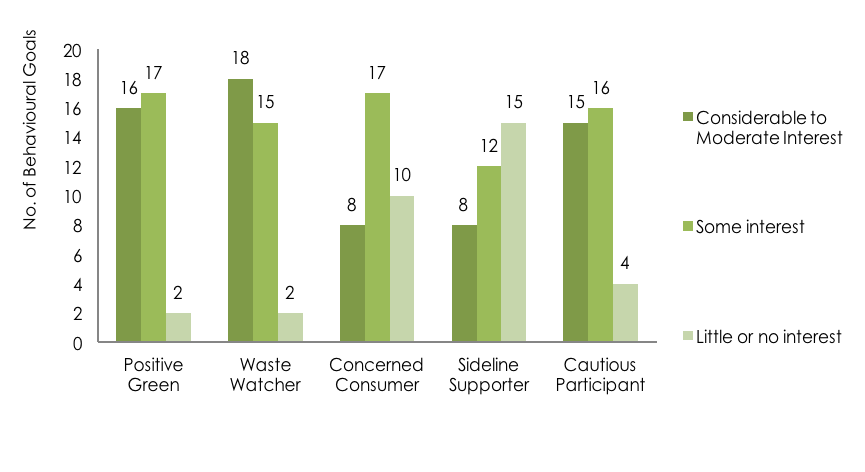

Figure 4 Participants Behavioural Goal Interest

Of the 35 behavioural goals proposed, 37% registered considerable to moderate willingness, and 44% some willingness across the population segments as illustrated in Figure 4 above. The measures of central tendency surrounding willingness behavioural goals might be considered equitable across the population segments.

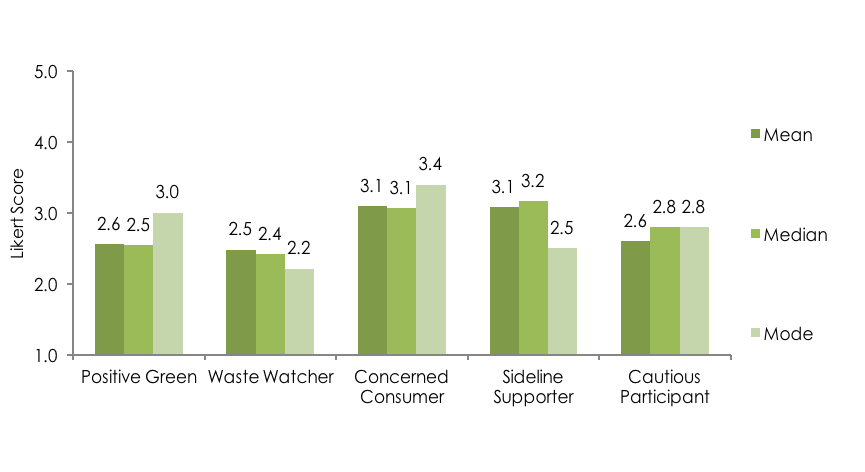

Figure 5 Willingness Behaviour Goals Measures of Central Tendency

Analysis shown in Figure 5 above reveals an opportune level of motivation whereby behavioural goals always performed returned a mean willingness of 2.17, on-cue 2.43, predictable schedule 2.63, at-will 2.64, one-time 2.68, for a period of time 3.17 and one-time leading to obligation 3.61. Cessation behavioural goals returned a mean willingness of 2.54, increasing the behaviour frequency, intensity or duration 2.69, existing or familiar behaviour 2.81, new or unfamiliar behaviour 2.83 and decreasing behaviour 2.94. Discussion surrounding the significance of each goal is beyond the scope of this document. In summary obligatory and periodic goals entailed a commitment to improving social capital, and decremental goals entailed sacrifice, while familiar or incremental goals on cue are seen as the most favorable.

Conclusion

Previous reductionism poorly framed value held in behaviour change by limiting the view as to what entails value in sustainability, undermining the complexity of reducing energy use in the home, which is contingent upon habitual change by the occupants. The needs of a person have undergone changes that have affected a change of energy use habit, and influenced by obsolescence in the social domain, individualistic barriers to change remain in place. This study suggests that the motivated state person's has also changed. In response, designers can choice-edit in support of the motivation state of persons to adopt small catalytic sustainable modes of change. Designers and producers possess the means to overcome barriers to individual change through reflexive social interaction. By striving for stronger pro-environment construction legislation and choice editing out the means for poor habitual energy use, it is possible to make effective small energy-use step changes well. The semantics of the framework behaviours require increased focus and refinement in order to inform design decisions to match the behaviour change; this study is seen as a new method for thinking about, and designing around, energy-use behaviour in buildings. This will entail further discussion and comparison of supporting willingness to change in favour of greater social capital and sustainable energy-use behaviours.

Works Cited

Baudrillard, J. (1996). The System of Objects (2nd Edition ed.). (J. Benedict, Trans.) London, UK: Verso.

Brook Lyndhurst. (2007). Public Understanding of Sustainable Energy Consumption in the Home: Final Report to the Department of Environment Food and Rural Affairs. UK Government, DEFRA. London: Brooks Lyndhurst.

Brynjarsdottir, H., Hakansson, M., Pierce, J., Baumer, E. P., DiSalvo, C., and Sengers, P. (2012). Sustainability Unpersuaded: How Persuasion Narrows our Vision of Sustainability. Critical Perspectives on Design (pp. 947-956). Austin: CHI 2012.

Corner, A. (2012). Promoting Sustainable Behaviour (1st Edition ed.). Oxford, Oxfordshire, UK: Do Sustainability.

DEFRA. (2007). A framework for pro-environmental behaviours. Retrieved April 16, 2014, from gov.uk: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/a-framework-for-pro-environmental-behaviours

Druckman, A., and Jackson, T. (2012). What is the carbon footprint of a decent life? In H. Herring (Ed.), Living in a Low Carbon Society in 2050 (1st Edition ed., pp. 51-55). Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Fogg, B. J. (2009). A Behaviour Model for Persuasive Design. Persuasion 09. Claremont: Persuasion 09.

Herring, H. (2009). Sufficiencey and the Rebound Effect. In S. Sorrell, and H. Herring (Eds.), Energy Efficiency and Sustainable Consumption; The Rebound Effect (2nd Edtion ed., pp. 224-238). Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Herring, H., and Sorrell, S. (2009). Introduction. In S. Sorrell, and H. Herring (Eds.), Energy Efficiency and Sustainable Consumption; The Rebound Effect (2nd Edition ed., pp. 2-16). Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Jackson, T. (2005). Motivating Sustainable Consumption; A review of evidence on consumer behaviour and behavioural change. University of Surrey, Centre for Environmental Strategy. Sustainable Development Research Network.

McKenzie-Mohr, D., Hargroves, K., Desha, C., and Reeve, A. (2010). Identification and Assessment of Homeowner Behaviours Related to Reducing Residential Energy Demand: Report to the Townsville CitySolar Community Capacity Building Program. Griffith University, The Natural Edge Project. Townsville: Townsville City Council.

Moraveli, N., Akasaka, R., Pea, R., and Fogg, B. J. (2011). The Role of Commitment Devices and Self-shaping in Persuasive Technology. CHI 2011 (pp. 1591-1596). Vancover: CHI 2011.

Sorell, S. (2009). The Evidence for Direct Rebound Effects. In S. Sorrell, and H. Herring (Eds.), Energy Efficiencey and Sustainable Consumption; The Rebound Effect (2nd Edition ed., pp. 23-35). Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Keep in Touch

WITH SOCIAL MEDIA UPDATES